Fredric Jameson, Yale French Dept PhD and Professor, Dies on September 22

Please see YFS Managing Editor Nichole Gleisner’s tribute.

Quoting from his NYT obituary (by Clay Risen), “Fredric Jameson graduated with a degree in English from Haverford College in Pennsylvania in 1954 and then went traveling in Europe, where he first encountered Western Marxist theory. He returned after a year to pursue a Ph.D. in literature from Yale; he graduated in 1959 with a dissertation on the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

Mr. Jameson taught at Harvard; the University of California, San Diego; Yale; and the University of California, Santa Cruz, before arriving at Duke in 1985. He remained on its faculty at his death.”

Please see berlow a NYT article by A.O. Scott

An Appraisal

For Fredric Jameson, Marxist Criticism Was a Labor of Love

The literary critic, who died on Sunday at age 90, believed that reading was the path to revolution.

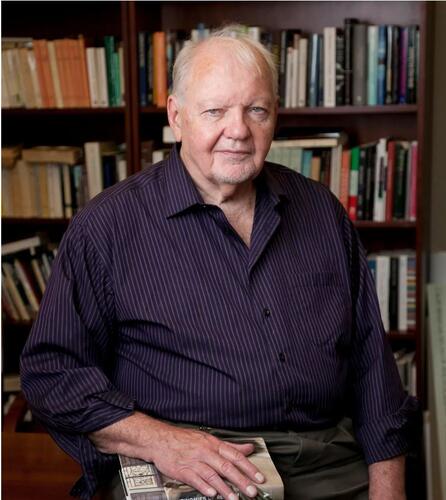

Fredric Jameson in 1988. His considerations of Balzac and Philip K. Dick, of Sartre and cyberpunk, of Proust and pop art are animated by enthusiasm and skepticism, by an engagement no less passionate for being unremittingly cerebral.

Duke University

At the time of his death, at 90, on Sept. 22, Fredric Jameson was arguably the most prominent Marxist literary critic in the English-speaking world. In other words, he was a fairly obscure figure: well-known — revered, it’s fair to say — within a specialized sector of an increasingly marginal discipline. I don’t say that to diminish his importance, but rather to make a case for it.

Jameson, hired by Duke with much fanfare in 1985 after teaching at Harvard, Yale and U.C. Santa Cruz, was an academic celebrity, a charismatic scholar in an era of professorial superstardom. Even so, he never sought to become a public intellectual in the manner of some of his American colleagues and French counterparts. You did not expect to see his face on television or find his byline on a newspaper opinion page. While his work was informed by a disciplined and steadfast political point of view — according to the essayist and Stanford professor Mark Greif, he was a Marxist literary critic “in a conspicuously uncompromising way” — it was not pious, dogmatic or ostentatiously topical.

Marxism was, for Jameson, both a mode of analysis and an ethical program. The novels, films and philosophical texts he wrote about — and by implication his own work too — could only be understood within the social and economic structures that produced them. The point of studying them was to figure out how those structures could be dismantled and what might replace them.

In many ways, though, Jameson was as much a traditionalist as a radical. His prose is dense and demanding, studded with references that testify to a lifetime of deep, omnivorous reading. For all his eclecticism he was, to a perhaps unfashionable degree, a literary critic, most at home in the old-growth forests of 19th- and 20th-century European literature, tapping at the trunks of the tallest timbers: Gustave Flaubert, Stéphane Mallarmé, James Joyce, Thomas Mann.

His considerations of Balzac and Philip K. Dick, of Sartre and cyberpunk, of Proust and pop art are animated by enthusiasm and skepticism, by an engagement no less passionate for being unremittingly cerebral. He was never sentimental about the writers and artists he studied, but there is no question that he loved them. Why else would he deliver a thrilling reading of “the two most boring chapters in ‘Ulysses’”? Or write a whole book about the odious Wyndham Lewis? What I mean is that he was, above all, a critic.

I’d like to say something about why, as a critic, Jameson mattered to me. And maybe, more generally, to the nonacademic, not necessarily Marxist brand of criticism that I and some of my comrades try to practice in the throes of late capitalism, a phrase he helped popularize.

The characteristic Jamesonian sentence is stubbornly resistant to quotation — a long, intricate play of subordinate clauses and rhetorical reversals, sweeping generalizations and granular examples, embedded in a paragraph of baroque complexity, romantic grandeur and classical coherence — but there is one, just two words long, that I’ve always thought would make a great inspirational forearm tattoo.

“Always historicize!” Those are the opening words of “The Political Unconscious,” Jameson’s 1981 book on “narrative as a socially symbolic act.” He identifies “this slogan” as “the one absolute and we may even say ‘transhistorical’ imperative of all dialectical thought.”

The first page of the preface, and we’re already deep in the weeds! But hang in there: For all the bristling abstraction of the language, the principle is straightforward, even common-sensical.

If you are a critic, professional or otherwise, the task before you is to make sense of an artifact of the human imagination — a poem, a painting, a dish of pasta, a Netflix docuseries, whatever. What does it mean? What is its value? To find the answers, it helps to know something about where it came from. Who made it? Under what conditions? For what purpose?

Those may not be specifically Marxist questions, but they are historical questions, and they begin a process of inquiry that may lead to Marxist conclusions. That love sonnet or fast-cooling plate of rigatoni is neither isolated nor static: It exists in relation to (for starters) other works of literature and gastronomy, and it changes over time. And so, of course, do you. Reading a Shakespeare sonnet in middle age is not the same as studying it in school, and what it means in the 21st century is not what it meant in the 17th. The noodles your grandmother served on Sunday are not the ones you will order at Olive Garden on Wednesday night.

Mapping that system and tracking its changes is the work of what Jameson calls “dialectical thought.” It’s a lot of work. To historicize your dinner you will need to take account of the voyages of Marco Polo, the European conquest of the tomato, the story of Italian immigrants in America and the rise of The New York Times cooking app. But of course there is, properly speaking, no pasta without antipasto; no primo piatto without a secondo; no dinner without dessert. Those matters will also need to be investigated. And we have not even raised the issue of gluten or the possibility of grated Parmesan. Or, more seriously, the unequal distribution of food in a consumer economy.

Welcome to the dialectic! Buon appetito! The point of this parody of Jamesonian method is not to mock a mighty intellect but to demystify some of his ideas, to translate them into a less forbidding idiom. (Transcoding; demystification; cognitive mapping: These are all terms in the Jameson lexicon.) Not that reading him could ever be easy: Criticism, as he understood it, could never be, because of the complexity of its objects and its need to perpetually revise, refine and question its own procedures.

To my mind, nobody did this as doggedly — or should I say as dialectically, with such a clearly articulated sense of the intellectual stakes — as Jameson.